Old Engli.sh

The Portal to the Language of the Anglo-Saxons

Did you enjoy this article? Read another piece of Old-Engli.sh Trivia!

Inflected Infinitives? Sure enough, in Old English!

The infinitive after to had an inflectional ending in Old English.The Adventurous History of the Word Wales

Wales is a gorgeous country with lush green valleys, spectacular mountain tops and stunning sandy beaches. The etymology of its name, however, is far less flattering, albeit ancient and exciting. |  Where does the name 'Wales' come from? |

The Modern English word Wales has its origin in the prehistoric Nordic iron age

The history of the word Welsh takes us far back into the past, c. 500 B.C., to the time when Germanic tribes first started moving into Northern Germany from their homeland in Scandinavia. Here, they encountered, displaced and assimilated Celtic tribes. One of the most powerful Celtic people they met was called 'Volcae.' Caesar mentions them in his commentaries on the Gallic War:

"And there was formerly a time when the Gauls excelled the Germans in prowess, and waged war on them offensively […]. Accordingly, the Volcae Tectosages, seized on those parts of Germany which are the most fruitful […] and settled there." (Caesar’s Gallic War 6.24)

The Germanic new-comers then took over and generalized the name 'Volca' to refer to any foreigner or group of foreigners - primarily Celts or Romans, who spoke a foreign, non-Germanic tongue. The Latin letter v usually represents a w-like sound at the beginning of words. The Indo-European o shows up as a in the Germanic languages, as in Latin quod but Old English hwæt 'what' or Latin octo but Gothic ahtau 'eight.' Finally, the Latin symbol c corresponds to a Germanic fricative x later h. For example, Latin cordis - English heart or Latin centum - English hundred. Correspondingly, the Germanic speakers would eventually pronounce their freshly-borrowed word Volcae as walha. This reconstructed base can explain a large number of descendant reflexes in the Germanic languages.

Evidence for the Proto-Germanic word walha 'foreigner, stranger, Romance-speaker' comes from many literary sources

The earliest known attestation of the root walha appears in the form of a runic inscription on a gold coin called the 'Tjurkö Bracteate,' which was found in Sweden in 1817 and is dated to 400 to 650 AD. The word appears in the nominal compound walha-kurne, 'foreign-corn.' A foreign (Roman or Gallic) grain can be interpreted metaphorically as a gold coin. Therefore, walha-kurne appears to be a poetic paraphrase - a so-called kenning - for the bracteate itself:

In the West-Germanic languages, the a in walha was transformed into an e under the influence of a following i (for example Gothic harjis, but Old High German heri, Old English here 'army;' this also explains the difference between Modern English man - men, tale - tell etc.). Therefore, the adjective walhisk shows up as welisc from Middle High German on and still exists in Modern German as welsch 'strange.' The word is used particularly frequently in Swiss German, where Welschschweiz designates 'French-speaking Switzerland,' Welschgraben refers to a former Burgundian defensive barrier, or Churwelsch is the term for a Romansh dialect once spoken in the city of Chur.

There are many more examples that testify to the Proto-Germanic root walha, like the Modern Dutch word waals 'Waloon' for the predominantly French-speaking southern part of Belgium or the Old Norse adjective valskr 'French, Romance.' Even Wallachia, a region in Romania famous for Bram Stoker’s Dracula, or the Vlahs, an antiquated name for Romanians themselves, ultimately derive from the same base: Slavic speakers took over the word from German and continued the tradition to use it for foreign people, except that it was now applied to Romance speakers in Eastern instead of Western Europe.

In Great Britain the meaning of Welsh undergoes a more ferocious development

The Germanic tribes of the Angles, Saxons and Jutes invaded England in the fifth century and also brought along with them the word walha. They used it to refer to the local Romanized Celtic population. But the encounter between British Celts and Anglo-Saxons was not a peaceful one: The invaders quickly displaced, murdered or enslaved the Celtic-speaking peoples. Gildas, a sixth century British cleric, writes about his fellow Celtic countrymen:

"Some […] were murdered in great numbers; others, constrained by famine, came and yielded themselves to be slaves for ever to their foes, running the risk of being instantly slain, which truly was the greatest favour that could be offered to them. […] Others remained still in their country, committing the safeguard of their lives, which were in continual jeopardy, to the mountains, precipices, thickly wooded forests, and to the rocks of the seas." (Gildas' On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain, 25)

Even though the attackers were the newcomers to the land, they called the ancestral population the wealas, 'strangers.' The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records,

473 A.D. þa wealas flugon þa Englan swa fyr.

'473 A.D. the Welsh fled from the English like fire.'

607 A.D. And her Æþelfried lædde ferde to Legaceastre & þær ofsloh unrim Wealana. & swa wearþ gefylld Augustinus witegunge þe he cwæð, "gif Wealas nellaþ sibbe wið us, hie sculon æt Seaxena handa forweorþan."

'607 A.D. And this year Ethelfrith led a troop to Chester and there murdered a huge number of Welsh people and thus was fulfilled Augustine’s prophecy when he said, “if the Welsh don’t wish peace with us, they shall perish at the hands of the Saxons."'

More clearly than in other languages, walha took on the meaning not just of foreigner but of 'the other' in Old English; it became a term for an inferior race, worthy of enslavement. Without mercy or shame, the Anglo-Saxon invaders gradually forced the Welsh from the rich, arable plains of the East to the rough, barren mountains in the West. And these are still the regions where the English Celtic-speaking minorities live to this day, Wales '(the land of the) foreigners' and Cornwall, with Corn- referring to the original tribal name of the inhabitants and -wall from Old English 'foreigner.' Welsh comes from the corresponding adjective, welisc, wælisc 'foreign.'

Old English: Se Ebreiscea wealh, þe ðu hider brohtest, eode in to me þæt he me bysmrude

Latin: Ingressus est ad me seruus Hebræus, quem adduxisti, ut illuderet mihi.

Modern English: 'The Hebrew slave, whom you brought hither, came in to me to ridicule me.' (Genesis 39:17)

Another reference to Welsh as a slave comes from Riddle number twelve of the Exeter book. It asks for the name of a thing that first moves around on green meadows, but, once dead, is turned into thongs, shoes or wine flasks, which are then served and cleaned by Welsh slave girls. What could that be? Well, most scholars believe the answer to the riddle should be "leather."

The word wealh is also used in a racially discriminatory sense in the Laws of King Ine of Wessex from the late seventh century. The law assigns - even to free wealas - a lower social rank than to an Englishman, as the compensation paid for killing them was lower for the former than for the latter.

But the Anglo-Saxons also coined much more innocent expressions from the word wealh. For example, the compound walhhnutu - Modern English walnut - is first documented c. 1050. The nut is "foreign" because it was originally native to France and Italy.

All's Welsh that ends Welsh

The word Wales has a long, sometimes purely practical, sometimes more prejudiced history. But the meaning of 'serf' for wealh has long died out and the modern day usage of Welsh is often associated with positive connotations and noble attributes. After all, French managed to develop a proud tradition of l’esprit gaulois, despite the fact that this word, too, originally merely meant 'foreigner.' Go ahead and articulate the word Wales with similar pride and elation!

The history of the word Welsh takes us far back into the past, c. 500 B.C., to the time when Germanic tribes first started moving into Northern Germany from their homeland in Scandinavia. Here, they encountered, displaced and assimilated Celtic tribes. One of the most powerful Celtic people they met was called 'Volcae.' Caesar mentions them in his commentaries on the Gallic War:

"And there was formerly a time when the Gauls excelled the Germans in prowess, and waged war on them offensively […]. Accordingly, the Volcae Tectosages, seized on those parts of Germany which are the most fruitful […] and settled there." (Caesar’s Gallic War 6.24)

The Germanic new-comers then took over and generalized the name 'Volca' to refer to any foreigner or group of foreigners - primarily Celts or Romans, who spoke a foreign, non-Germanic tongue. The Latin letter v usually represents a w-like sound at the beginning of words. The Indo-European o shows up as a in the Germanic languages, as in Latin quod but Old English hwæt 'what' or Latin octo but Gothic ahtau 'eight.' Finally, the Latin symbol c corresponds to a Germanic fricative x later h. For example, Latin cordis - English heart or Latin centum - English hundred. Correspondingly, the Germanic speakers would eventually pronounce their freshly-borrowed word Volcae as walha. This reconstructed base can explain a large number of descendant reflexes in the Germanic languages.

Evidence for the Proto-Germanic word walha 'foreigner, stranger, Romance-speaker' comes from many literary sources

The earliest known attestation of the root walha appears in the form of a runic inscription on a gold coin called the 'Tjurkö Bracteate,' which was found in Sweden in 1817 and is dated to 400 to 650 AD. The word appears in the nominal compound walha-kurne, 'foreign-corn.' A foreign (Roman or Gallic) grain can be interpreted metaphorically as a gold coin. Therefore, walha-kurne appears to be a poetic paraphrase - a so-called kenning - for the bracteate itself:

| wurte | runoz | an | walha-kurne | heldaz | kunimundiu |

| worked | runes | on | foreign-corn | Held | for.Kunimund |

‘Held worked runes on [this] foreign-grain [=gold coin] for Kunimund’

|

Old High German documents record the adjective related to walha, variably spelled as walask, walahisk, walhisk etc. 'strange, foreign, Romance.' |

| Reconstruction of the Tjurkö Bracteate |

In the West-Germanic languages, the a in walha was transformed into an e under the influence of a following i (for example Gothic harjis, but Old High German heri, Old English here 'army;' this also explains the difference between Modern English man - men, tale - tell etc.). Therefore, the adjective walhisk shows up as welisc from Middle High German on and still exists in Modern German as welsch 'strange.' The word is used particularly frequently in Swiss German, where Welschschweiz designates 'French-speaking Switzerland,' Welschgraben refers to a former Burgundian defensive barrier, or Churwelsch is the term for a Romansh dialect once spoken in the city of Chur.

There are many more examples that testify to the Proto-Germanic root walha, like the Modern Dutch word waals 'Waloon' for the predominantly French-speaking southern part of Belgium or the Old Norse adjective valskr 'French, Romance.' Even Wallachia, a region in Romania famous for Bram Stoker’s Dracula, or the Vlahs, an antiquated name for Romanians themselves, ultimately derive from the same base: Slavic speakers took over the word from German and continued the tradition to use it for foreign people, except that it was now applied to Romance speakers in Eastern instead of Western Europe.

In Great Britain the meaning of Welsh undergoes a more ferocious development

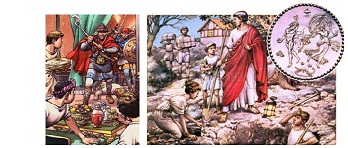

The Germanic tribes of the Angles, Saxons and Jutes invaded England in the fifth century and also brought along with them the word walha. They used it to refer to the local Romanized Celtic population. But the encounter between British Celts and Anglo-Saxons was not a peaceful one: The invaders quickly displaced, murdered or enslaved the Celtic-speaking peoples. Gildas, a sixth century British cleric, writes about his fellow Celtic countrymen:

"Some […] were murdered in great numbers; others, constrained by famine, came and yielded themselves to be slaves for ever to their foes, running the risk of being instantly slain, which truly was the greatest favour that could be offered to them. […] Others remained still in their country, committing the safeguard of their lives, which were in continual jeopardy, to the mountains, precipices, thickly wooded forests, and to the rocks of the seas." (Gildas' On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain, 25)

Even though the attackers were the newcomers to the land, they called the ancestral population the wealas, 'strangers.' The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records,

473 A.D. þa wealas flugon þa Englan swa fyr.

'473 A.D. the Welsh fled from the English like fire.'

607 A.D. And her Æþelfried lædde ferde to Legaceastre & þær ofsloh unrim Wealana. & swa wearþ gefylld Augustinus witegunge þe he cwæð, "gif Wealas nellaþ sibbe wið us, hie sculon æt Seaxena handa forweorþan."

'607 A.D. And this year Ethelfrith led a troop to Chester and there murdered a huge number of Welsh people and thus was fulfilled Augustine’s prophecy when he said, “if the Welsh don’t wish peace with us, they shall perish at the hands of the Saxons."'

More clearly than in other languages, walha took on the meaning not just of foreigner but of 'the other' in Old English; it became a term for an inferior race, worthy of enslavement. Without mercy or shame, the Anglo-Saxon invaders gradually forced the Welsh from the rich, arable plains of the East to the rough, barren mountains in the West. And these are still the regions where the English Celtic-speaking minorities live to this day, Wales '(the land of the) foreigners' and Cornwall, with Corn- referring to the original tribal name of the inhabitants and -wall from Old English 'foreigner.' Welsh comes from the corresponding adjective, welisc, wælisc 'foreign.'

|

Subsequently, the Old English word Welsh even allowed for its interpretation as 'slave.' For example, the Old English rendition of the Old Testament directly translates Latin seruus with wealh. |

|

| Romano-British Celts attacked by Anglo-Saxon raiders and burying treasure as they escape from the invaders |

Old English: Se Ebreiscea wealh, þe ðu hider brohtest, eode in to me þæt he me bysmrude

Latin: Ingressus est ad me seruus Hebræus, quem adduxisti, ut illuderet mihi.

Modern English: 'The Hebrew slave, whom you brought hither, came in to me to ridicule me.' (Genesis 39:17)

Another reference to Welsh as a slave comes from Riddle number twelve of the Exeter book. It asks for the name of a thing that first moves around on green meadows, but, once dead, is turned into thongs, shoes or wine flasks, which are then served and cleaned by Welsh slave girls. What could that be? Well, most scholars believe the answer to the riddle should be "leather."

The word wealh is also used in a racially discriminatory sense in the Laws of King Ine of Wessex from the late seventh century. The law assigns - even to free wealas - a lower social rank than to an Englishman, as the compensation paid for killing them was lower for the former than for the latter.

But the Anglo-Saxons also coined much more innocent expressions from the word wealh. For example, the compound walhhnutu - Modern English walnut - is first documented c. 1050. The nut is "foreign" because it was originally native to France and Italy.

All's Welsh that ends Welsh

The word Wales has a long, sometimes purely practical, sometimes more prejudiced history. But the meaning of 'serf' for wealh has long died out and the modern day usage of Welsh is often associated with positive connotations and noble attributes. After all, French managed to develop a proud tradition of l’esprit gaulois, despite the fact that this word, too, originally merely meant 'foreigner.' Go ahead and articulate the word Wales with similar pride and elation!

- Go back to the Old English Trivia Archive

- Read about Welsh servants in Riddle 12 from the Exeter Book

- Read Faul's (1975) study 'The Semantic Development of Old English wealh'