Old Engli.sh

The Portal to the Language of the Anglo-Saxons

Read another, randomly chosen, past Old-Engli.sh News article:

Lo! Dictionary of Old English unveils lovely Old English Words in L

February 2023

February 2021

Thousands of Words Added to the Corpus of Old English

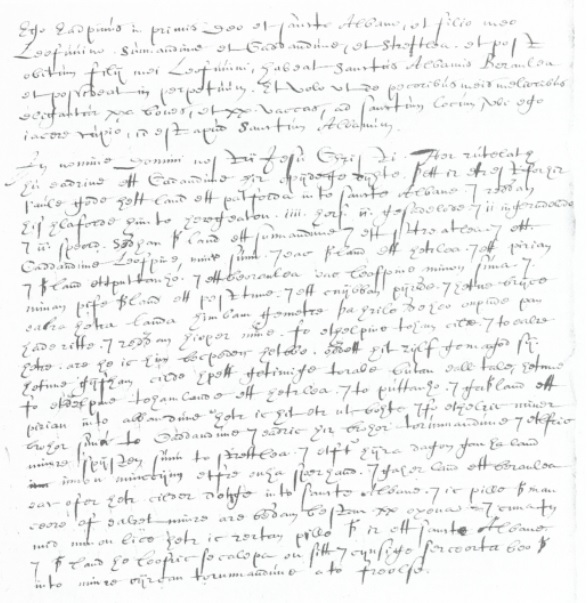

As a dead language, Old English has a finite number of text sources its native speakers wrote while they were alive. The only way to enlarge the Old English corpus is therefore to discover new manuscripts of previously unknown texts. Such discoveries are extremely rare and noteworthy events. Yet, the DOE’s Corpus of Old English has just accomplished such a feat – several new texts comprising thousands of words were added to their database in 2019. |  Manuscript Brussels, Bibliothèque Royale, 7965-73, f. 165r - a seventeenth century transcript of Old English charters now included in the Dictionary of Old English Corpus |

The new Old English writings have a remarkable history: Jesuit scholars, known as Bollandists, founded a library in Antwerp in the seventeenth century, accumulating, borrowing and transcribing texts they deemed important. It thus transpired that a number of Anglo-Saxon manuscripts passed through their hands as well, and they promptly copied them for their collection. The Bollandist movement was eventually suppressed, and one of the manuscripts containing transcripts of Old English, number 157, ended up in the Bibliothèque Royale in Brussels, where it remains to this day, now shelved as number 7956-73 (3723). It is this copy that includes as item vi on folios 151r-216v the new Old English texts.

What then are those previously unknown Old English texts? They are charters, Anglo-Saxon right-granting legal documents. They were copied off of a so-called cartulary from St. Albans. A cartulary is itself a copy of charters, usually thematically related to the foundation and privileges of an institution. Interestingly, the charters in question were largely known already, but only as Latin translations. It is only through the modern Bollandist transcript that we can read the original Anglo-Saxon vernacular versions for the first time. Sawyer’s Catalogue of Charters, first published in 1968, lists all known Anglo-Saxon charters, and thus permits a glimpse into the fascinating world of medieval English culture to the public. The following excerpt of the new Old English charters is taken from that catalogue (Sawyer number 1532):

(Charter S 1532, A.D. 1050. Will of Ulf)

The new texts include examples of several lexical items never before seen, such as ealdorcyre ‘suitable choice for a superior’ and geondra ‘farther, more distant’ (the ancestor of Modern English yonder, for which no Old English example was previously recorded). The latest Dictionary of Old English progress report thus deservedly celebrates the latest addition to their text collection.

The discovery makes one wonder what other lost text treasures may slumber on dusty library shelves around the world, just waiting to reveal themselves and their secrets...

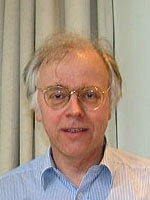

Portrait of Simon Keynes, who was largely responsible for the discovery and popularization of the new Old English texts. |

We owe it largely to the work of Simon Keynes, Elrington and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon emeritus, who studied and recognized the importance of these transcripts, that we can now read and enjoy these writings. |

What then are those previously unknown Old English texts? They are charters, Anglo-Saxon right-granting legal documents. They were copied off of a so-called cartulary from St. Albans. A cartulary is itself a copy of charters, usually thematically related to the foundation and privileges of an institution. Interestingly, the charters in question were largely known already, but only as Latin translations. It is only through the modern Bollandist transcript that we can read the original Anglo-Saxon vernacular versions for the first time. Sawyer’s Catalogue of Charters, first published in 1968, lists all known Anglo-Saxon charters, and thus permits a glimpse into the fascinating world of medieval English culture to the public. The following excerpt of the new Old English charters is taken from that catalogue (Sawyer number 1532):

| Ærest ic becweðe for mine sawle Gode 7 sancte Albane þæt land æt Eastune mid mete 7 mid mannon swa swa ic hit læne, 7 eallswa þæt land æt Oxawican, into þære halgan stowe æt sancte Albane þær ic licgan wille. | In the first place, I bequeath for my soul to God and St Alban the land at Aston, with produce and with men just as I lease it, and also the land at Oxwick, to the holy place at St Albans where I wish to be buried. |

The new texts include examples of several lexical items never before seen, such as ealdorcyre ‘suitable choice for a superior’ and geondra ‘farther, more distant’ (the ancestor of Modern English yonder, for which no Old English example was previously recorded). The latest Dictionary of Old English progress report thus deservedly celebrates the latest addition to their text collection.

The discovery makes one wonder what other lost text treasures may slumber on dusty library shelves around the world, just waiting to reveal themselves and their secrets...

- Read Simon Keynes' seminal paper A lost cartulary of St Albans Abbey

- Find more OE news at www.oenewsletter.org

- Read the full Dictionary of Old English 2019 Progress Report