Old Engli.sh

The Portal to the Language of the Anglo-Saxons

Did you enjoy this article? Read another piece of Old-Engli.sh Trivia!

The Good Luck of the Beowulf Manuscript

The Anglo-Saxon epic poem Beowulf, one of the most treasured gems of English literature, has been preserved in only one single manuscript.Apollonius of Tyre - The first Novel written in English

It is a gripping story of exile and love, separation and reunion, an exciting romance, providing diverting entertainment throughout antiquity and the Middle Ages, an exploration of piracy, shipwrecking, incest, deception, murder, enforced prostitution and adventure. And it also happens to be the first piece of fictional prose writing in the English language – the Old English Apollonius of Tyre. |  Apollonius returns to Tarsis (from a 15th c. manuscript, ÖNB 2886, f. 9r) |

Apollonius is persecuted by the evil king of Antioch, after he discovers the incestuous relationship between the monarch and his daughter. On the run, the hero gets shipwrecked in Cyrenaica, wins the favour of the local king, and marries his daughter, a princess whose name is never revealed. Through unlucky circumstances, Apollonius believes both his wife and his new-born daughter dead, but is eventually reunited with his family.

The text is believed to have been composed originally in Greek in the 3rd century. The Old English version is based on a now lost Latin rendition and survives in a unique 11th century manuscript (Cambridge Corpus Christi College 201, folios 131-45), which contains otherwise mostly legal, juridical and homiletic texts associated with Archbishop Wulfstan of York.

Apollonius was remarkably popular in the Middle Ages; while the Old English translation was created first, subsequent versions are known in the vernaculars of places as diverse as Spain, Russia and Iceland. Chaucer mentions the tale disapprovingly in his Man of Law’s Tale and Shakespeare used it as the basis for the play Pericles Prince of Tyre.

Why this fictional text was translated from Latin into the Anglo-Saxon vernacular to begin with remains a mystery. Old English prose covered many subjects, but always served the purpose of informing and exhorting. Writing was largely confined to the Church in the Middle Ages, which employed it for administrative purposes and liturgy, the greater glory of God and the salvation of souls, not for entertainment. Writing was also an expensive business – a large manuscript required elaborately prepared skins from a considerable number of animals – so that only useful things were committed to script. Why then does this unique secular prose text exist among the mass of otherwise utilitarian Old English literature?

Apollonius of Tyre might simply be an exercise in translation and hence utilitarian after all. Although writing was a serious clerical occupation pursued by priests of various holy orders in monasteries, it had to be learned like any other trade. The young scribe may have found it more diverting to practise his skills in Latin rendition with a fictional piece than, say, a saint’s life. This may not be such an absurd idea since there are various awkward translations, errors, and corrections. For example, the title has been left incomplete after its ending had been scraped away:

Editors have filled in the missing words in various ways, for example “Apollonius, the Tyrian prince”. Did the inexperienced translator spot a mistake here but forgot to correct it?

Consider also the very last sentence of the text:

Are these the words of an overly self-conscious scribe who knows his work is far from perfect, trying to hide its blemishes?

On the other hand, the translation of the text, even within the monastic context of Old English text culture, may be a deliberate choice. The worldly piece may have been of interest to the monastic text producers for its edifying moral message, for Apollonius’ saint-like qualities, for his stoic suffering of hardship and pain. This would explain why there is more restraint in the Old English translation, where sex and love have been toned down considerably in comparison to other versions. Furthermore, the middle part of the romance is missing, about one third of the overall text. Perhaps it has fallen victim to monastic censorship. The lacuna might have included elements too spectacular and salacious for the devout medieval priest to bear.

Whatever the reason for its existence, the Old English Apollonius of Tyre has been a great read for the last 1000 years and will continue to enrich the lives of everybody enjoying Anglo-Saxon literature.

The text is believed to have been composed originally in Greek in the 3rd century. The Old English version is based on a now lost Latin rendition and survives in a unique 11th century manuscript (Cambridge Corpus Christi College 201, folios 131-45), which contains otherwise mostly legal, juridical and homiletic texts associated with Archbishop Wulfstan of York.

Apollonius was remarkably popular in the Middle Ages; while the Old English translation was created first, subsequent versions are known in the vernaculars of places as diverse as Spain, Russia and Iceland. Chaucer mentions the tale disapprovingly in his Man of Law’s Tale and Shakespeare used it as the basis for the play Pericles Prince of Tyre.

Why this fictional text was translated from Latin into the Anglo-Saxon vernacular to begin with remains a mystery. Old English prose covered many subjects, but always served the purpose of informing and exhorting. Writing was largely confined to the Church in the Middle Ages, which employed it for administrative purposes and liturgy, the greater glory of God and the salvation of souls, not for entertainment. Writing was also an expensive business – a large manuscript required elaborately prepared skins from a considerable number of animals – so that only useful things were committed to script. Why then does this unique secular prose text exist among the mass of otherwise utilitarian Old English literature?

Apollonius of Tyre might simply be an exercise in translation and hence utilitarian after all. Although writing was a serious clerical occupation pursued by priests of various holy orders in monasteries, it had to be learned like any other trade. The young scribe may have found it more diverting to practise his skills in Latin rendition with a fictional piece than, say, a saint’s life. This may not be such an absurd idea since there are various awkward translations, errors, and corrections. For example, the title has been left incomplete after its ending had been scraped away:

heronginneð seo gerecednes beantióche þā unge sæligan cingce 7be apolonige þam…

‘Here begins the Narrative about Antiochus, the wicked King, and about Apollonius, the…’

Editors have filled in the missing words in various ways, for example “Apollonius, the Tyrian prince”. Did the inexperienced translator spot a mistake here but forgot to correct it?

|

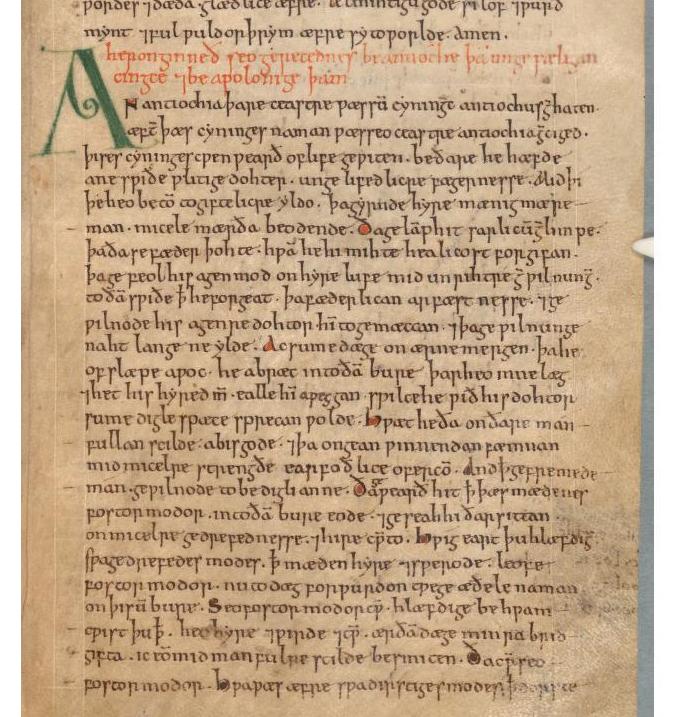

The first page of Apollonius of Tyre (CCCC 201, f. 131) The incomplete title of the novel is clearly visible in red ink. Manuscript Description Mansucript Contents |

Consider also the very last sentence of the text:

and gif hi hwa ræde. ic bidde þæt he þas awændednesse ne tæle. ac þæt he hele swa hwæt swa þar on sy to tale.

‘And if anyone read it I beg that he blame not the translation, but that he conceal whatever may be therein blameworthy’

Are these the words of an overly self-conscious scribe who knows his work is far from perfect, trying to hide its blemishes?

On the other hand, the translation of the text, even within the monastic context of Old English text culture, may be a deliberate choice. The worldly piece may have been of interest to the monastic text producers for its edifying moral message, for Apollonius’ saint-like qualities, for his stoic suffering of hardship and pain. This would explain why there is more restraint in the Old English translation, where sex and love have been toned down considerably in comparison to other versions. Furthermore, the middle part of the romance is missing, about one third of the overall text. Perhaps it has fallen victim to monastic censorship. The lacuna might have included elements too spectacular and salacious for the devout medieval priest to bear.

Whatever the reason for its existence, the Old English Apollonius of Tyre has been a great read for the last 1000 years and will continue to enrich the lives of everybody enjoying Anglo-Saxon literature.

- Read Apollonius of Tyre in Old English and with Thorpe's (1834) translation

- Go to the Old English Trivia Archive

- More external links on Old English texts, including Apollonius, in the Links section